Hidden Traps on the Internet, Max Out Your Defense!

Child Welfare League Foundation (CWLF) released “2023 Survey on Children and Youth Online Safety and Digital Literacy in Taiwan.”

On average, children and youth spend nearly five hours online after school, and this screen time could potentially double during summer vacation.

Amidst the long vacation and scorching summer days, spending time indoors with air conditioning and scrolling through smartphones seems to have become the summer routine for children and youth. According to this year's survey conducted by CWLF, the average daily internet usage time for children and youth (excluding time spent on homework and online classes) is 4.6 hours, reaching a weekly total of 32.2 hours. This is a significant increase compared to the 27.2 hours per week recorded in the 2020 survey. Deducting their school hours, it's almost as if they spend most of their free time online, especially during the extended school break. It's easy to imagine that the screen time for using digital devices will increase substantially during the long break when there's no school. The spokesperson of CWLF, Hong-Wen Li, explained the ongoing concern for online safety among children and youth. The boundary between online and offline life has become increasingly blurred in today's world, particularly for this generation of digital natives. Internet life has become an integral part of their daily routine. However, what worries us is whether we have equipped these children and youth with sufficient "digital literacy" to navigate the online world filled with inappropriate content such as violence, hatred, pornography, as well as threats from scams, fake news, and encounters with strangers. Summer vacation has already been ongoing for over a week, and as a parent, you might be increasingly concerned about your children falling into the trap of excessive internet usage. CWLF released the "2023 Survey on Children and Youth Online Safety and Digital Literacy in Taiwan," along with specific solutions presented in the "Beat Box Online Safety Treasure Chest." This initiative follows four steps: BE-AWARE, EXPLORE, AGREE, and TEACH. It aims to accompany children and youth to have a joyful and safe summer break.

Children and youth have a high demand for online social interaction, which exposes them to three major internet risks: financial scams, deceptive relationships, and personal information exploitation.

The current survey conducted by CWLF revealed that children and youth primarily use YouTube as their main online platform, followed by various social media platforms, namely Instagram, Messenger, Facebook, and TikTok, with usage rates of 74.2%, 71.9%, 68.2%, and 58.6% respectively. Additionally, the survey also finds that over half (50.6%) of children and youth would create online social media accounts before the age of 11, granting them a new digital identity and a sense of autonomy. Hence, it's evident that besides accessing information, social interaction is a fundamental need when kids are online. Although engagement with social media platforms also holds positive value for children, such as staying connected with family and friends regardless of distance, receiving psychological support, and even discussing various topics including reports and assignments, the nature of online social interactions extends beyond real-world relationships. It can involve online friends who may have never been met in person, blurring the lines between defining friends and strangers. According to the 2023 survey by CWLF, 39.4% of children and youth believe that "if I chat pleasantly with a stranger online, I consider them a friend." This figure has significantly grown by more than 16.6% compared to the 2020 survey, where only 21.8% shared this sentiment. This decrease in caution towards online strangers suggests that children and youth are becoming more trusting of unknown online acquaintances, consequently amplifying the risks in the online world. As a response to these online hazards, CWLF categorizes them into three main types: financial scams, deceptive relationships, and personal information exploitation.

Crisis One: Financial Scams. On average, more than one in every five children and youth (22.8%) have experienced being scammed.

The most common scenario involves a significant disparity between the purchased product and the product shown in online images, accounting for over half (58.6%) of cases. Following that is accidentally clicking on phishing (or scam) links, which constitutes 37.2% of incidents. Moreover, over 21.1% reported instances where the product received from an online purchase was completely different from what was expected.

Crisis Two: Deceptive Relationships. One-fifth of respondents have encountered special requests from online acquaintances, with 59% of them being asked for romantic involvement.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Protective Services Department in 2022, cases involving the production and distribution of explicit content involving minors constituted over 86.4% of the total cases under the Child and Youth Sexual Exploitation Prevention Act. In this survey, 21.4% of the respondents reported having encountered special requests from online acquaintances. Among these requests, the most common was for a "romantic relationship," accounting for nearly 59.3%. Additionally, requests for "video calls" and "individual meetings" were reported by 51.3% and 50.9% respectively, both exceeding half of the respondents. The survey also found that sharing intimate photos happens between children and youth, it showed that 10% of children and youth or their classmates and friends have received nude photos or videos(received by themselves 5.6%, received by classmates 5.4%), some children and youth or their classmates have even shared their nude photos or videos with online acquaintances(sent by themselves 0.9%, sent by classmates 4.6%). These findings indicate a lack of caution among children and youth regarding intimate photos.

Crisis Three: Personal Information Exploitation. Forty-one percent of children and youth have provided their personal information to online acquaintances.

Among all respondents, 33.1% indicated that they have shared personal information for "private IG or LINE accounts," making it the most common type. This is followed by "real name" at 24.7%, "personal photos" at 22.5%, and "class or school information" at 14.1%. Further analysis based on different age groups revealed that senior high school students are notably more likely to share personal information compared to junior high school students. This suggests that protection of personal information does not necessarily improve with age among children and youth.

So, which types of children and youth are more likely to fall into the aforementioned online crises? Spokesperson Hong-Wen Li stated that the current survey found that children and youth who use TikTok, IG, and YouTube are more likely to experience negative online behaviors and encounters. Furthermore, those who easily regard online strangers as friends tend to have more negative experiences. What's concerning is that some children and youth who struggle with developing normal face-to-face relationships can still construct desired social interactions and communication in virtual online environment. Leveraging the anonymity of the internet, children and youth might seek emotional support or solace. As a result, they might easily trust online acquaintances who display kindness and concern, increasing their vulnerability to become victims online, often without realizing the risks they're putting themselves in. Further investigation by CWLF into the willingness of children and youth to seek help when facing online crises revealed that 12.8% of them are unlikely to seek help for any issues. They prefer to solve problems on their own, which is a worrying aspect of their behavior.

Youth representatives Roy and Doris shared their personal experiences of falling victim to online scams and leaking of intimate photos. They emphasized the importance of establishing correct online safety knowledge and urged schools to teach practical ways of handling online threats to prevent or minimize harm. During the press conference, Roy explained that during his middle school years, he sent money to a stranger online to buy tickets, but not only did he not receive the tickets, he was also immediately blocked by the individual. Afterward, he shared his experience of being scammed online, and other users shared similar suspicious accounts, highlighting the recurring issue of online scams. Roy also mentioned that while schools do educate about avoiding scams, they often focus on common methods like ATM transfers, which may not effectively address scenarios involving online behavior by minors. Doris shared a story where she saw a friend's initimate photo leaked online. Upon comforting her friend, she learned that her friend had followed an online acquaintance's instructions to engage in a video call that involved revealing private areas, which was then screenshot and shared. This case was handled by the authorities, and Doris hoped to remind other minors to avoid trusting strangers online and to prioritize protecting their privacy.

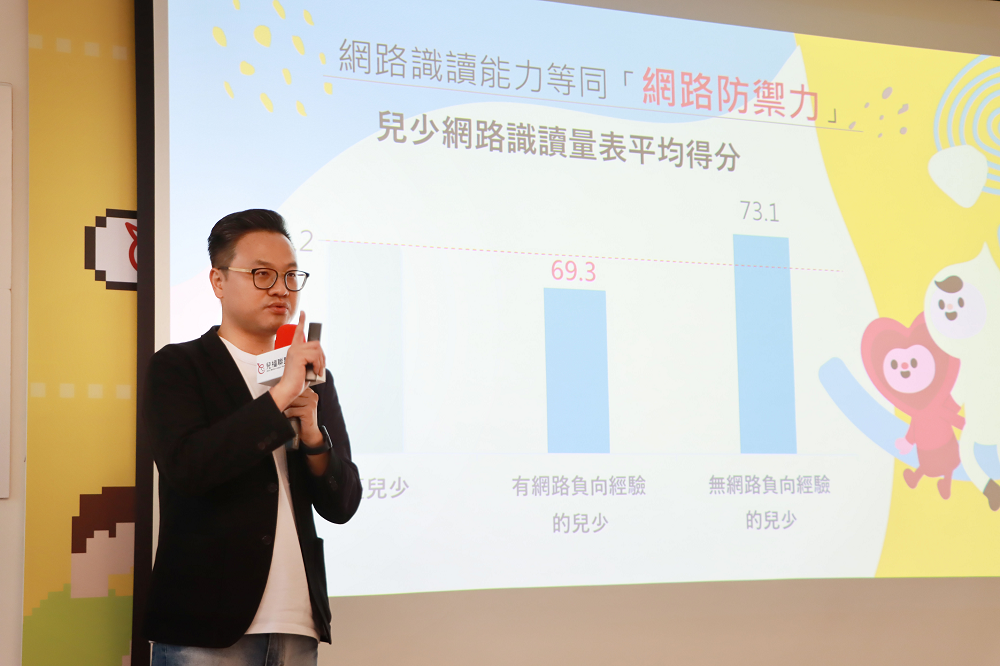

The average online defense capability among minors in Taiwan is 71.2. A lower defense capability corresponds to a higher level of online risk.

"Digital literacy" refers to an individual's knowledge and ability to recognize and understand the potential impacts of internet information across various dimensions. When equipped with this knowledge and skill, individuals can avoid being negatively influenced by inappropriate online content. Digital literacy is equivalent to having "online defense" capability, which can protect children and youth from online risky behaviors. CWLF has developed a "Children and Youth Digital Literacy Scale" to understand the correlation between digital literacy and online risks among children and youth. The results revealed that the average score on the digital literacy scale in Taiwan is 71.2. Among the attitude-related questions, the most common misconceptions were related to not recognizing that the sequence of content in most online videos is deliberately arranged and not being skeptical about everything the media says. This suggests that children's ability to protect themselves online is quite limited. Notably, there is a strong correlation between digital literacy and negative online behaviors and experiences. Those with no negative online experiences had an average score of 73.1 on the digital literacy scale, significantly higher than the average score of 69.3 for those with negative online experiences. This indicates that children and youth with better digital literacy have higher levels of self-protection online and thus lower relative online risks.

Furthermore, the survey also found that the primary sources of online safety knowledge for children and youth are "Google search," accounting for 71.9%. This is followed by "teachers" at 69.7% and "parents" at 65.1%, both having more than sixty percent of responses. "YouTube/TikTok" is the next source at 53.0%. Notably, 14.0% of children and youth rely solely on online searches without discussing with their teachers or parents. These individuals tend to exhibit significantly poorer performance in digital literacy and are more susceptible to being misled by misinformation. This highlights the crucial role that teachers and parents play in guiding and educating children, and that their guidance is a key factor in fostering digital literacy.

It's not just about the latest smartphones; fostering digital literacy is the most precious gift we can give to children and youth.

Children's online safety advocate and writer, Zhe-bin Huang, emphasized that technology has given this generation of children both a gift and an infinite temptation and burden. He highlighted the importance of "companionship" to bridge the digital gap between parents and children. He suggested that parents engage in discussions with their children and collaboratively set reasonable "screen time limits," covering the total hours spent on television, laptops, tablets, and smartphones. Different rules can be applied to different age groups in these discussions. During this process of companionship, in addition to understanding children's online preferences, parents should also guide them on how to discern reliable sources of information and teach them to protect themselves online. Children should be educated not to follow online acquaintances' instructions or share personal information. According to CWLF's survey, those children who discuss online safety with their parents tend to have better digital literacy. Interestingly, the study also found that parents' restrictions on their children's internet usage time do not significantly impact their digital literacy. Therefore, discussing the potential hazards of the internet with children is essential for enhancing their online defense capabilities.

Zhe-bin Huang, a writer and media figure deeply concerned about child and youth online safety, who is also a father of two children, attended the press conference and shared his observations. He highlighted the significant emphasis that foreign countries place on understanding how technology tools affect children and youth, as well as their mental well-being, privacy protection, and digital upbringing. Mr. Huang proposed an analogy based on parenting habits. He noted that when parents take their children to a park to play, they typically accompany them closely to ensure safety and often provide guidance on using equipment and interacting with others. However, when it comes to the online world, parents often allow children to explore on their own. He shared a case from a classmate of his elementary school child, who had created a YouTube channel and gained attention, leading to provocative and harassing comments from unfamiliar online users. This classmate felt hesitant to inform parents and teachers about the situation, highlighting that many children do not know how to handle interactions with strangers online. Mr. Huang also pointed out that parents rarely discuss with their children how to deal with actions like liking, provoking, or shaming on the internet. Consequently, children and youth lack the necessary skills, awareness, and knowledge to navigate online situations effectively.

Mr. Huang also shared methods from abroad regarding digital upbringing. These methods involve collaborative efforts among parents, taking turns to guide children in understanding digital topics such as effective use of YouTube and internet searching. He suggested instilling the concept and habit of a "3C caregiver" from an early age. Similar to parents accompanying children to a park, this involves providing companionship and guidance to children, negotiating internet usage time and content with them. In addition to the family's role as the primary line of defense, for vulnerable families or those with multi-generational parenting, schools serve as the second line of defense. They assist children by providing relevant internet education materials and manuals to help them navigate online spaces safely.

CWLF advocates for the following measures:

- Recommending the establishment of a dedicated governmental agency responsible for child and youth online safety. This agency should be equipped with sufficient manpower and an independent budget. Drawing inspiration from UK Council for Internet Safety, a mechanism should be developed to integrate efforts across government, law enforcement, businesses, and third-party organizations, ensuring comprehensive protection for child and youth online safety.

- Suggesting that schools provide child-appropriate solutions in response to online threats, using scenario-based and case-based teaching methods. This approach aims to increase children and youth's awareness of online safety and equip them with knowledge about various risks and corresponding countermeasures.

- Encouraging parents to utilize various tools, including the "Digital Literacy Assessment Chart" developed by CWLF. This tool allows parents to assess whether their children belong to a high-risk group for online activities. Additionally, leading discussions about online safety with children can incorporate the use of the "Beat Box Online Safety Treasure Chest," which employs four steps: BE-AWARE, EXPLORE, AGREE, and TEACH. This helps children protect their online privacy and teaches them how to respond when encountering diverse online interactions.(Link: https://www.cylaw.org.tw/about/advocacy/10/433)

Note: This survey was conducted through an online questionnaire from May 1st to May 31st, 2023. A total of 12,967 individuals responded to the questionnaire, with 12,643 responses considered valid. Within the valid sample, 68.7% were junior high school students, 31.3% were senior high school students; 47.3% were male, 51.2% were female, and 1.5% identified as other genders.